| |

Blog/book excerpt Blog/book excerpt

from

Ken Burnett, writer, publisher and occasional fundraising consultant.

This article is reproduced from

The Field by the River by Ken Burnett, published in hardback and paperback by Anova Books Limited, London.

Now available in Kindle, download and enjoy today.

‘The key thing, Ken, is this... was he really sussing you out, figuring that you were not going to draw the dogs’ attention?’

In the original text there follows an adventure In the original text there follows an adventure

with the ugliest creature of the forest, some

mid-air sex, a dance of death, a meeting with

the gruesome ichneumon wasp and a feature on

the secret lives of bees. Then, the issue of animal intelligence is taken up again.

For more about the field by the river read The deaf dumb and blind kid, Animal intelligence, The onset of Alzheimer’s and rough sex down by the river.

For more on the book

The Field by the River, click here.

Ken Burnett can be followed by clicking the button above. Ken Burnett can be followed by clicking the button above.

More blogs on fundraising and communication

• Is it time for Twitter suicide?

• The future of fundraising.

• Is direct mail dead?

• The donor pyramid isn’t well either.

• The fundraising dream team

• The indispensable guard book.

• Prepare for the fundraising trustee.

•The transformational fundraising entrepreneur.

Home page

|

|

From chapter 10, May. Dumb mutts and birdbrains:

the relative intelligence of different species

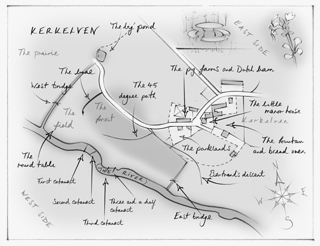

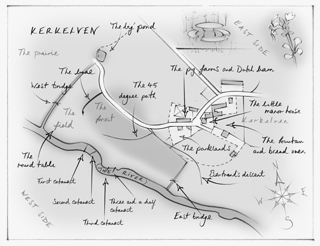

A theme, or at least a question, emerged from my observations in the field by the river: are the animals, birds and insects of Kerkelven clever, or are they merely the slaves of instinct and learned behaviour? It seems plain to me that the issue is not whether or not they are smart, but how smart? And is their version of clever the same as ours?

In the first few hundred metres there’s been a close encounter, a life saving, a major confrontation, a near fatality, two surprise discoveries and an urge to fall about laughing.

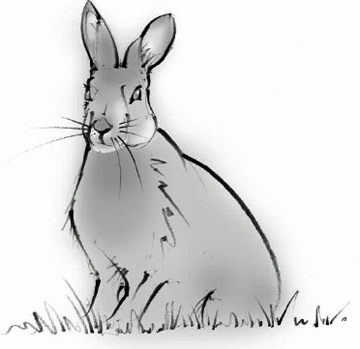

It’s been such a corker of a morning as would make the darkest, bleakest heart to soar. We had a charming chance meeting first thing this morning down by the big pond, though once again I’m the only one who noticed it. The dogs were snuffling around in the mud and mire as I was standing on the narrow path between field and pond, just idly allowing them time in which to do this, when lolloping along towards us there came a great big hare. He didn’t spot any of us until he was right on top of us. He saw the dogs first just as I saw him, then his eyes met mine and he slowed to a deliberate, measured walk. For a couple of seconds he held me with a piercing glare. I looked at him and he at me and I realised that in that look he was assessing me, deciding whether or not I would give his game away. I felt then that in that look he had sussed me to the very core of my being. He saw I was a bystander, that I didn’t present any danger. And I saw that he wasn’t going to turn and go back whence he’d come which, had he concluded that I was a danger, he would surely have done. But no. He’d realised that the dogs all had their backs to him, so were ignorant of his presence. Continuing to study me closely he then, incredibly, accelerated past almost on tiptoe. He made absolutely no noise, just shot by me, so close I could have touched him.

All three dogs remained in blissful ignorance as we set off into the wood, me feeling very bucked by my meeting with a hare with such attitude, style and, apparently, intentional assessment ability.

We hadn’t progressed more than a hundred metres when Mortimer’s sudden veer to the left and increased acceleration...

In the original text there follows an adventure

with the ugliest creature of the forest, some

mid-air sex, a dance of death, a meeting with

the gruesome ichneumon wasp and a feature on

the secret lives of bees. Then, the issue of

animal intelligence is taken up again.

Some weeks after the chance encounter with a hare that I describe in the epic walk, I happened to be staying with my friend Michael Devitt, distinguished professor of philosophy at the City University of New York Graduate Center, with whom I share not only a passion for fine wines and prolonged argument but also, I discovered, an emerging interest in animal intelligence. Michael is now teaching a new course at his university on animal cognition. His analysis of the meaning of my meeting with the hare seemed both profound and insightful.

‘The key thing, Ken,’ he pronounced in his cultured Australian lilt, ‘is this. Had the hare merely learned, as he is clearly able to do, that in the presence of both dogs and humans he should be more afraid of the dogs? Or was he really sussing you out, figuring that you were not going to draw the dogs’ attention?

‘Sussing your intention,’ he opined, ‘would take a lot of intelligence because it requires insight into another’s mind. A test for this is, what difference to the hare’s behaviour would it make whether he had sussed you or not? Suppose it hadn’t, would it have behaved differently?’

‘How would I know?’ I queried. This response seemed to please the learned professor, as apparently it illustrates precisely the kind of dilemma that cognitive ethologists – the people who study such things – find most thrilling.

‘Fear of the dogs rather than the human,’ he went on, ‘could just be learned behaviour and the ability – which hares clearly have – to make a simple judgement and a choice. But sussing your intention would almost certainly imply a process of rational inference; that the hare has an ability to appreciate not just that a third party – i.e. you – has a reasoning process,but what’s more, that he the hare can attempt to predict what the outcome of that process might be.’

To answer this, of course, we’d really need to find some way of interrogating the hare or at least of observing him in controlled or contrived situations either in the wild or in the laboratory. As none of this is likely, all information on the incident has to come from me, for other than the hare, I was the only one to see what happened. Though my memory of the encounter is clear, I can’t say for sure that I know what was in the hare’s mind. But at the time I thought I did...

Partial extract from pages 320 to 335 of The Field by the River, © Ken Burnett 2009. The illustrations are by Juliet Percival.

Ken Burnett’s other books mainly focus on fundraising, communication and the wider universe. They include the classic Relationship Fundraising: a donor-based approach to the business of raising money and The Zen of Fundraising. For information on all Ken’s books, click here. To order your copy of The Field by the River, £12.99 (US$21.00) plus P&P hard cover, £7.99 (US$13.00) paperback, click here.

|

|

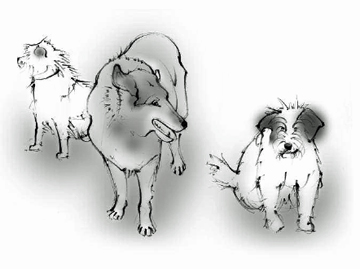

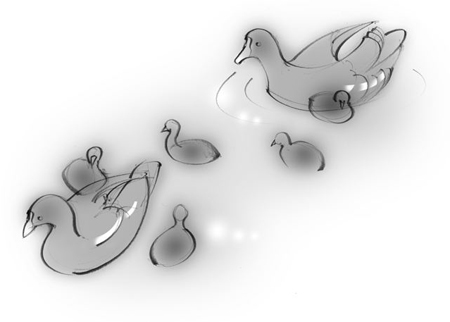

Are Mortimer, Max and Syrus, above, any smarter than the moorhens, those perfect parents who nevertheless lose at least some of their offspring every year, for the silliest of reasons?

Kerkelven looks peaceful but there's more blood and intrigue per square metre here than in the Tower of London. You have to part a few bushes or lift a few stones to get at it. Or catch a hare.

Clever and fast, sure. But with intentional assessment ability?

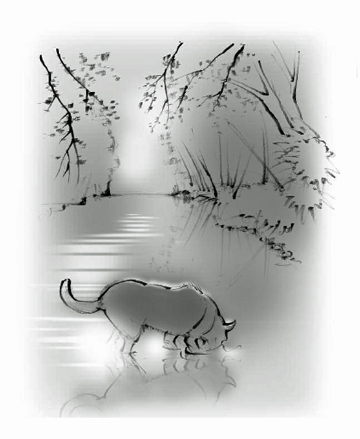

Mortimer in the river: Not brilliant, perhaps. But superbly happy. Mortimer in the river: Not brilliant, perhaps. But superbly happy.

Want to comment on any of this? Have your say here. Email your comment now to Ken.. Want to comment on any of this? Have your say here. Email your comment now to Ken..

|

Mortimer in the river: Not brilliant, perhaps. But superbly happy.

Mortimer in the river: Not brilliant, perhaps. But superbly happy.